Economics

They won’t like the name and they’ll surely hate the stagflation, so can China’s economic bosses avoid… ‘Japanification’?

There are familiar structural issues facing the Chinese economy in 2023 China’s property sector crisis is among several headwinds vs … Read More

The…

- There are familiar structural issues facing the Chinese economy in 2023

-

China’s property sector crisis is among several headwinds vs growth

-

Aviva Investors note potential parallels with Japan’s “lost decades”

New analysis from Aviva released ahead of 2023 suggests China’s decades of growth burn is not only at an end, but structural deficits like its ageing population, rising debt and a crisis in the key domestic property market has put the whiff of stagnation around the middle kingdom’s mid-term outlook.

According to Avivam China risks following Japan’s path from runaway growth to financial crisis and stagnation.

The big question is can Xi Jinping’s government rebalance the economy and change course?

The Chinese Communist Party Congress in October was a grand spectacle. But the political ceremony took place against a darkening economic backdrop.

China’s year-to-date GDP growth stood at three per cent as of the third quarter, according to official data, lagging the government’s annual target of 5.5%

The proximate cause of the growth slowdown is President Xi Jinping’s ongoing zero-COVID policy, which dictates stringent lockdowns to contain coronavirus outbreaks and is stoking widespread anger. In late November, a deadly fire at an apartment block in Xinjiang province sparked protests in several cities, after claims strict lockdown procedures had been a factor in the death toll.

But China also faces deeper structural problems and according to Alistair Way, head of equities at Aviva Investors, the population is ageing quickly and Beijing is struggling to manage an economic transition away from debt-fuelled investment towards consumer-led growth.

A crisis in China’s property sector could yet spread contagion into other areas of the economy.

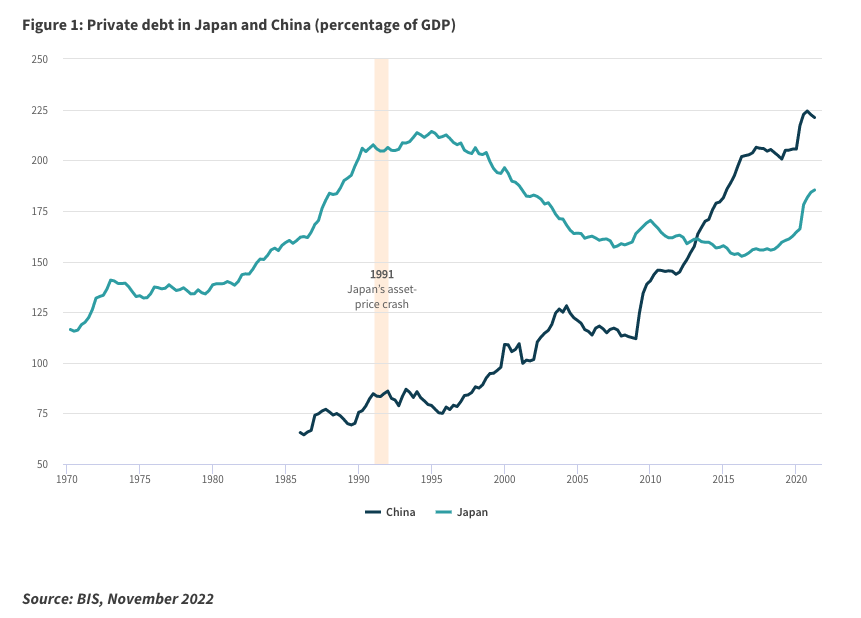

These factors have led some experts to draw comparisons between China and neighbouring Japan. In 1991, the bursting of an asset-price bubble brought Japan’s high-growth era to an abrupt end, inaugurating a period dubbed the “lost decades”. As in China, Japan’s ageing demographics are inhibiting government efforts to rouse the economy.

“Although there are differences, it makes sense to worry about the ‘Japanification’ of China,” says David Nowakowski, senior multi-asset and macro strategist at Aviva Investors.

“The demographic trends are very similar and there is also a property crisis, as there was in Japan in the 1990s. It’s possible China’s high-single-digit growth phase is coming to an end.”

1. Rising Debt

While China is still poorer than Japan was at the time of its crash – per-capita GDP is around $12,000, less than half the $29,000 figure for Japan in 1991 – there are undeniable echoes of Japan’s debt-driven boom in the 1980s.

After Deng Xiao Ping’s market reforms began in 1978, China developed quickly on huge infrastructure spend over the subsequent decades.

Rising debt’s not a problem when the economy is going gangbusters and growing fast enough to absorb any credit shocks – but Aviva suggests that’s no longer the case.

Check out this kind of household debt growth.

The Carnegie Endowment’s Michael Pettis, professor of finance at Peking University’s Guanghua School of Management, estimates Chinese investment started becoming less productive at some point between 2006 and 2008.

Since then, debt has risen sharply, the growth rate has moderated and exports decreased in importance relative to investment.

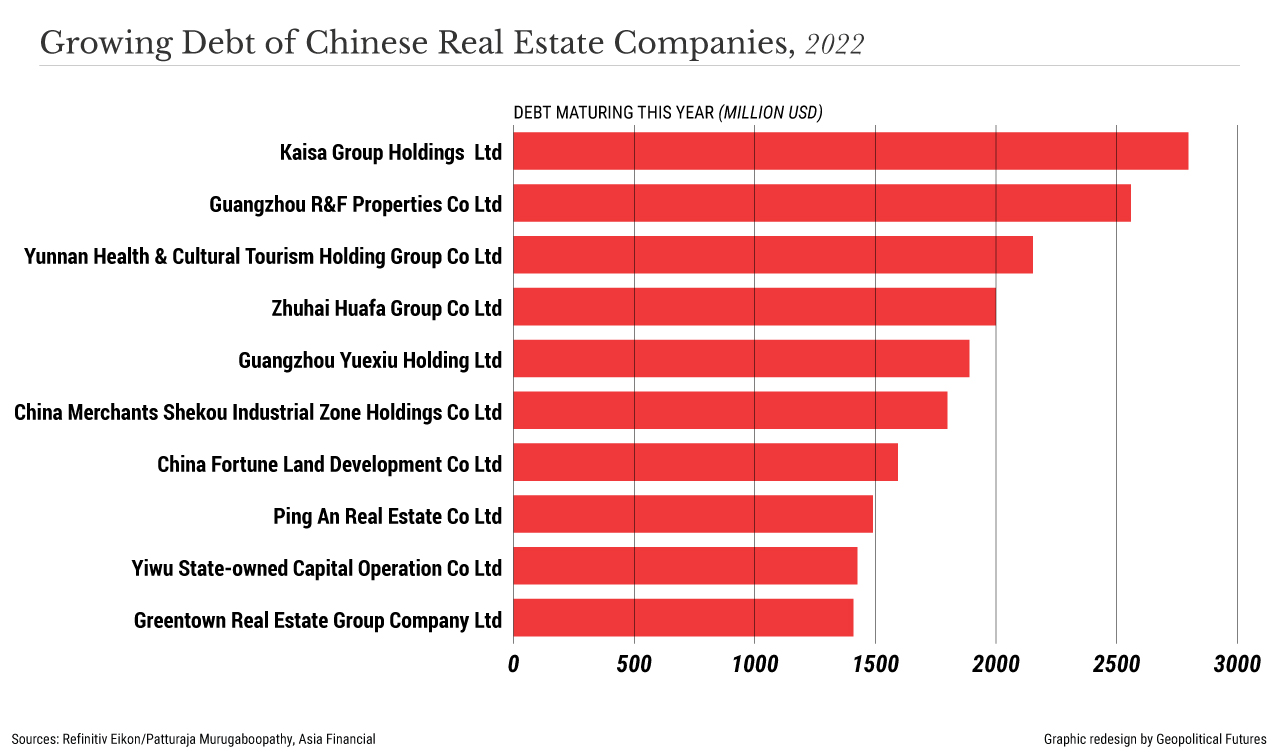

2. Property crisis

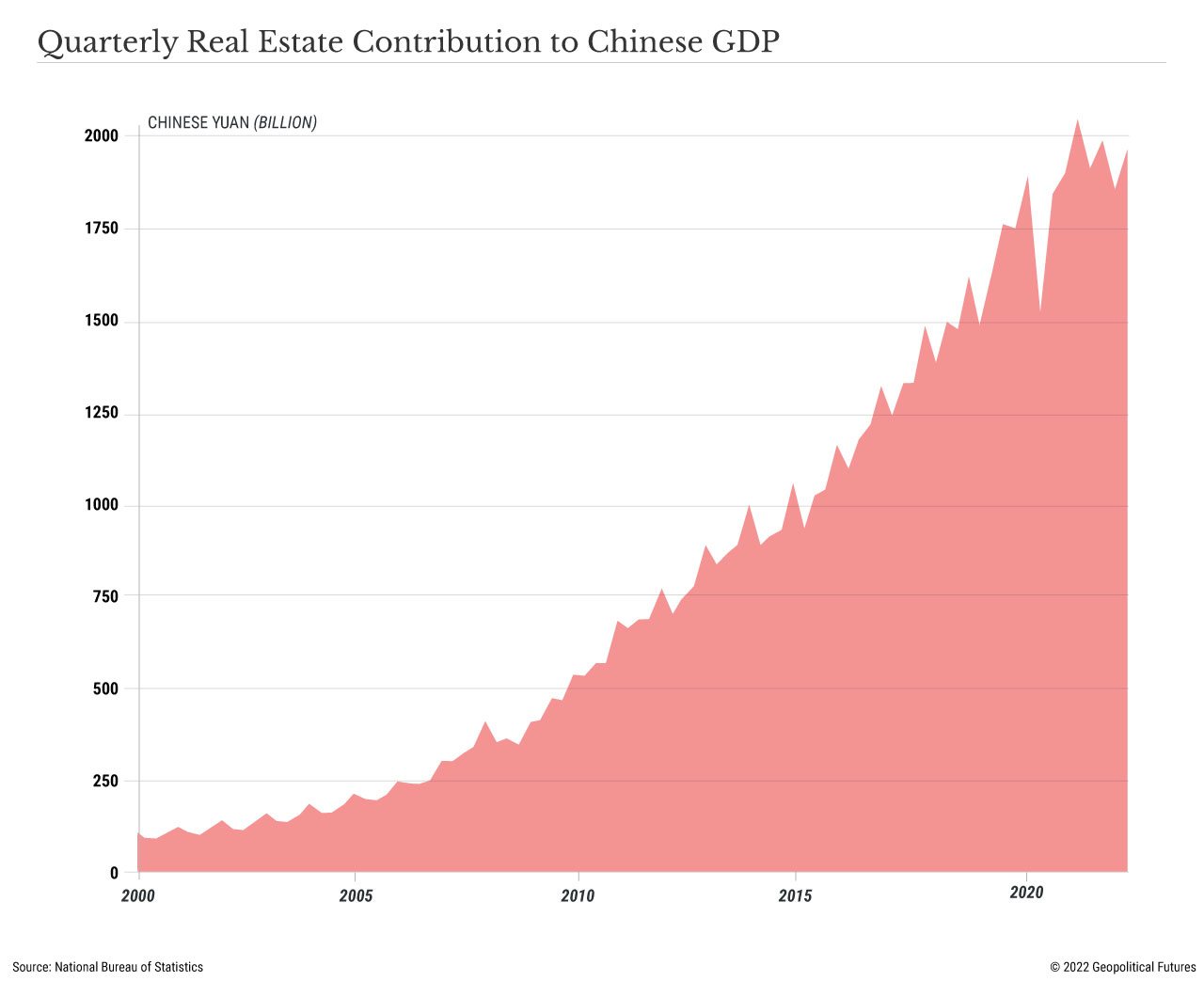

Around 25-30 per cent of China’s GDP is now associated with property or related industries, according to data from the Peterson Institute for International Economics.2 But many developers are struggling under high levels of debt.

China Evergrande, the country’s biggest developer, defaulted on an international debt payment in December 2021.

Alarmed by leverage in the sector, the government announced “three red lines” to restrict borrowing in August 2020 and house prices have since begun to decline. This has created problems not just for developers but also local governments, whose revenues from land sales have fallen, leaving them less able to service their own debts.

While the property bubble resembles Japan’s in some respects, a precise repeat of Japan’s 1991 crisis is unlikely says Amy Kam, portfolio manager for emerging market debt at Aviva Investors.

The centralised Chinese government has more control over the economy than Japan’s did and will try to enact a gradual and controlled deleveraging process that may weigh on growth over a prolonged period.

3. Domestic demand and demographics

The big question now is what, if anything, will pick up the slack as a longer-term driver of growth as debt-driven investment wanes.

Beijing has acknowledged the need to rebalance the economy by promoting a more sustainable growth model based on domestic demand rather than debt. But private consumption’s share of GDP stands at a lowly 39%, compared with 68% in the US.

Enacting a transfer of wealth and income from local governments and state-owned enterprises to consumers will be politically difficult.

Another problem is that wealth in China is often held in property; as house prices fall, consumers may feel compelled to tighten their belts rather than open their wallets. And the rapid ageing of China’s population could pose a further obstacle to the government’s efforts to rebalance the economy.

Increased costs for health and social care will put a drag on government and household budgets and could inflict further economic damage on top of the unpopular zero-COVID policy.

A recent study by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) shows an ageing population tends to lower the natural rate of interest.

Low rates of interest restrict the scope a central bank has to revive the economy during periods of crisis, as Japan has found.

Deflation is another risk.

But an ageing population is not all bad news. China’s population is ageing partly because its citizens are healthier and living longer.

Chinese life expectancy actually increased by 0.2 years in 2020 from the year prior. By contrast, US life expectancy fell 1.8 years in 2020 over the same period.

And it is possible a decline in the working-age population may push up wages by boosting the bargaining power of those in the workforce, potentially helping improve consumption.

4. Investment implications

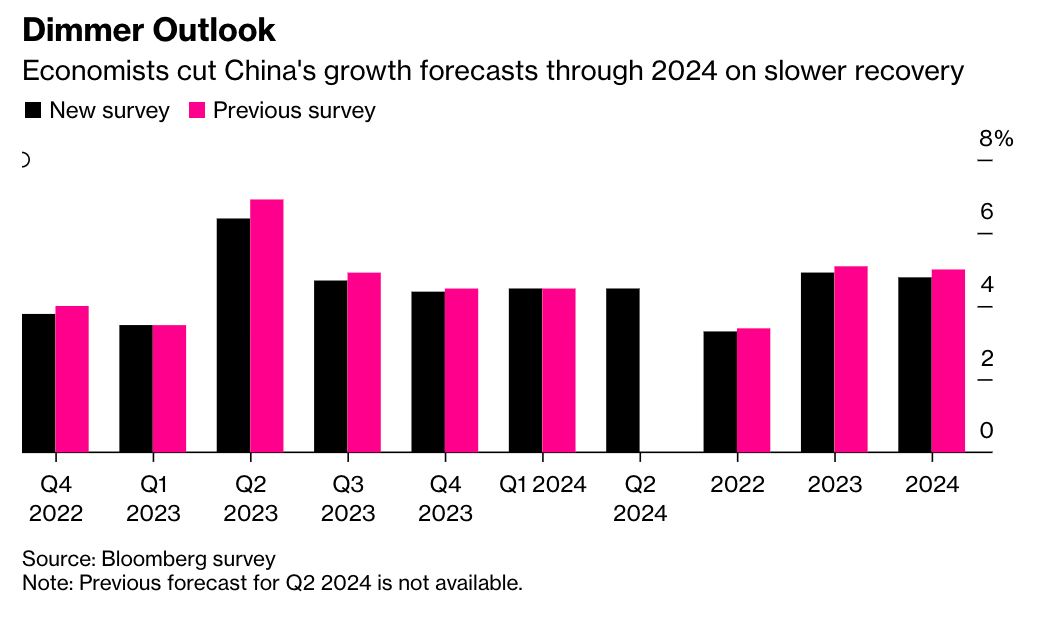

While China could yet avoid Japanification over the long term, many experts are revising down their outlooks for Chinese growth. The consensus among economists surveyed by Bloomberg is that growth will remain below five per cent for each year through 2024.

Given its size, a slowdown in China growth is of obvious significance to the global economy.

Nowakowski says the biggest impact of a Chinese slowdown would be felt among its main trade partners in emerging markets, along with a few advanced economies, including Germany.

The vulnerabilities in China’s’s property sector carry obvious risks for investors in its domestic markets. Equity investors are concerned about potential spill-overs and the state of corporate balance sheets, along with the ongoing impact of the zero-COVID policy.

Over the longer-term, however, the need to promote greater domestic consumption could create opportunities, argues Alistair Way.

“China is likely to want to incentivise a shift of savings away from property towards financial instruments, which could benefit Chinese financial services firms. Rising domestic consumption would also benefit domestic companies in other sectors including consumer electronics and electric vehicles.”

The post They won’t like the name and they’ll surely hate the stagflation, so can China’s economic bosses avoid… ‘Japanification’? appeared first on Stockhead.

deflation

stagflation

monetary

markets

policy

central bank

bubble

stagnation

Argentina Is One of the Most Regulated Countries in the World

In the coming days and weeks, we can expect further, far‐reaching reform proposals that will go through the Argentine congress.

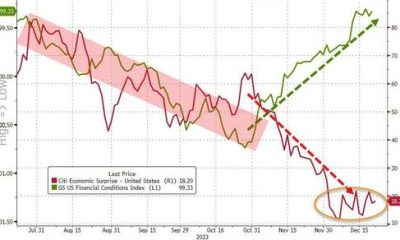

Crypto, Crude, & Crap Stocks Rally As Yield Curve Steepens, Rate-Cut Hopes Soar

Crypto, Crude, & Crap Stocks Rally As Yield Curve Steepens, Rate-Cut Hopes Soar

A weird week of macro data – strong jobless claims but…

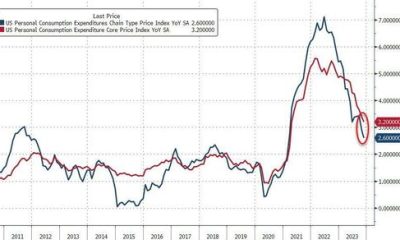

Fed Pivot: A Blend of Confidence and Folly

Fed Pivot: Charting a New Course in Economic Strategy Dec 22, 2023 Introduction In the dynamic world of economics, the Federal Reserve, the central bank…