Economics

The World In 2023: What Is Priced In?

The World In 2023: What Is Priced In?

Authored by Dario Perkins via TS Lombard,

Bonds and equities appear to be priced for a soft-ish landing…

The World In 2023: What Is Priced In?

Authored by Dario Perkins via TS Lombard,

-

Bonds and equities appear to be priced for a soft-ish landing this year

-

Consensus could be missing the reflexivity of the recessionary process

-

But a “no landing” scenario is possible as well, with higher terminal rates

By now, investors should be fully aware of the macro consensus for this year – especially as most sellside economists are essentially making the same prediction. As a special service to TS Lombard clients, I selflessly perused a dozen Year Ahead reports in December and provided a summary so that our readers could spend their holidays engaged in more entertaining pursuits. But if recent performance is anything to go by, the shelf life of these publications is likely to be rather short. Often, by mid-January, the sellside consensus is already staler than a leftover turkey dinner with all the trimmings, a glass of flat champagne, and a slice of dry Christmas Panettone. So, we should be on the lookout for some big surprises during the next couple of weeks. And with this in mind, it is useful to ask what is currently “priced in” and where the biggest risks lie.

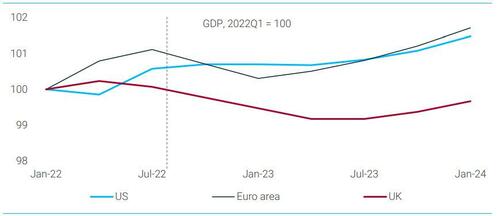

Chart 1: Consensus expects broad stagnation – aka a soft landing

Source: Bloomberg consensus, TS Lombard

To further distill the consensus at the end of December – i.e. to summarize my summary of the sellside outlook – most economists, investors and policymakers believed the following:

-

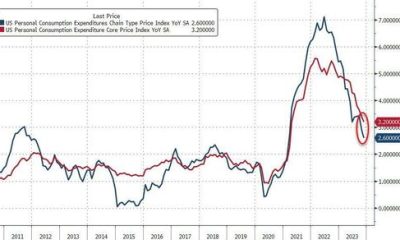

Inflation has peaked and will trend towards – but not reach – central banks’ targets:

-

All the major economies will broadly stagnate in 2023, or experience mild recessions:

-

Those that are forecasting recessions, including central banks, expect the mildest recession in history because acute labour shortages will prevent widespread job losses;

-

Central banks will stop hiking rates but will pursue “tighter for longer” policies. The bond market is priced for rates cuts in 2023 but central-bank watchers generally disagree.

It is important to re-emphasize the mildness of the downturn expected by the consensus. While a lot of sellside economists clearly see the marketing benefits of peddling their “bold recession calls”, almost nobody in the latest Bloomberg survey expects even an averagely bad downturn this year, let alone a crash on a par with what happened in 2008. To illustrate the point, the average change in US unemployment during recessions is 3%pts. There is not a single economist in the consensus who expects an increase in unemployment of that magnitude by the end of 2024. In fact, the smallest increase in US unemployment during any official recession was 1.9% pts (1961) and only 4/55 forecasts are for something as bad as that by 2024.

The Fed’s forecast, meanwhile, is even tamer than that of the consensus. And, as I showed previously, Fed staff have an unbroken record of seriously underestimating the severity of every US economic downturn.

Chart 2: Expecting the mildest US recession in history

Source: Bloomberg consensus, TS Lombard

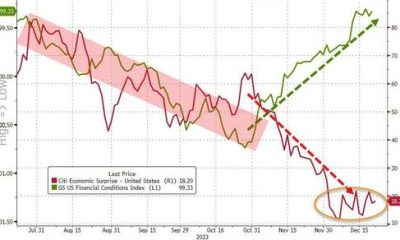

So, it is hard to escape the idea that – despite all the market spin and emphasis on “downside risks” – the consensus is forecasting something close to a soft landing. Stagnation perhaps, but not deep contraction, especially not by historical standards. And, arguably, this is also the only scenario that can reconcile current market pricing. Equity valuations plunged in 2023 but earnings expectations have been remarkably resilient, particularly compared with what usually happens in a recession (Chart 3). At the same time, although the yield curve remains deeply inverted, bond markets are not anticipating the sort of central-bank response that typically follows a genuine cyclical contraction. Since the average US recession comes with a 15% decline in profits, 500+bps of Fed rate cuts, and a blowout in credit spreads, markets today seem to be priced for a mid-course monetary “correction”: inflation plunges, central banks cut rates back to neutral, and the economy somehow muddles along. This would be a repeat of 1995, or perhaps 1998.

If we are looking for ways the consensus could be wrong, the obvious risk is a much deeper than expected global recession. And this is not unthinkable. Recessions come with strong reflexivity, which is why economists always end up chasing GDP and employment lower with a succession of downward revisions to their forecasts. Job losses in one systemically important sector tend to reduce spending and corporate revenues in other sectors, triggering further redundancies and a general loss of confidence. Or sometimes something “breaks” in financial markets, prompting a more precipitous decline in asset prices. Currently, the property sector is the most likely trigger for a consensus-busting recession. Tighter monetary policy has already caused serious strains in a number of housing markets; and it is possible central banks are underestimating the cumulative impact of their actions (which come with a lag). Yet, with a few exceptions, the risks associated with the property sector look muted compared with previous recessions – especially subprime.

Chart 3: Not your average recession for corporate earnings

Source: BEA national accounts profits, S&P 500 EPS forecast, TS Lombard

While it is possible the consensus is underestimating the severity of the global downturn in 2023, we think the more likely “risk” is, in fact, what we call the “no landing” scenario.

One point we emphasized all last year is that this is not a normal business cycle. Instead, massive distortions – first from the pandemic and then from the war – have created a largely artificial stagflationary environment, which could reverse as those same distortions unwind. In the context of the 2023 outlook, this reversal could mean both lower inflation and stronger economic activity than any investor currently dares contemplate – at least for a while. And it would be ironic if Goldilocks returned, albeit briefly, just at the point where everyone had given up on her. The problem, of course, is that the “no landing” scenario would ensure that labour markets remain tight, leaving the “fundamental economic imbalance” (at least as central banks see it) unresolved. Far from cutting interest rates, the authorities would probably resume policy tightening later in the year, perhaps after a brief pause. So not as bullish at it seems. But, in the wake of what was one of the worst years for investors in more than a century, at least our no landing scenario might provide a brief period of respite for battered financial markets – before the beatings resume.

Tyler Durden

Thu, 01/05/2023 – 06:30

inflation

monetary

markets

policy

interest rates

fed

monetary policy

stagnation

Argentina Is One of the Most Regulated Countries in the World

In the coming days and weeks, we can expect further, far‐reaching reform proposals that will go through the Argentine congress.

Crypto, Crude, & Crap Stocks Rally As Yield Curve Steepens, Rate-Cut Hopes Soar

Crypto, Crude, & Crap Stocks Rally As Yield Curve Steepens, Rate-Cut Hopes Soar

A weird week of macro data – strong jobless claims but…

Fed Pivot: A Blend of Confidence and Folly

Fed Pivot: Charting a New Course in Economic Strategy Dec 22, 2023 Introduction In the dynamic world of economics, the Federal Reserve, the central bank…