Economics

Lessons From a Chaotic Year

Olga and Hugo review their predictions and explore what surprised them in 2022, focusing on gross domestic product (GDP), interest rates, earnings growth,…

Olga and Hugo review their predictions and explore what surprised them in 2022, focusing on gross domestic product (GDP), interest rates, earnings growth, energy prices, and the dollar.

Hugo: Olga, this has been quite the year for us to review. Some major events happened that very few people expected. Others were more foreseeable, but they might not have played out exactly as forecast.

As is customary for us, let’s start by talking about economic growth. What do you think nominal GDP will have been in the United States this year? And do you believe that it could be the source to help us understand many other things that happened in 2022?

Olga: Traditionally, Hugo, economists focus on real GDP growth, but you’re quite right that understanding nominal growth is also important, in part because corporate sales and earnings are usually discussed in nominal terms.

Our forecast for nominal GDP incorporates expectations for both growth and inflation. We were on the right track by anticipating the significant deceleration in growth. But growth slowed in line with what we and many others expected, while inflation was higher. On balance, nominal GDP actually held up better than we had predicted, but that was driven by higher inflation than we expected at the beginning of the year.

The suddenness of the Russia-Ukraine conflict, the unpredictability, is what drives the inflationary impulse.

Hugo: What were the drivers of inflation?

Olga: Inflation was so strong not least because it was exacerbated by geopolitical tension. The Russia-Ukraine conflict certainly didn’t help here. The suddenness of the conflict, the unpredictability, is what drives the inflationary impulse.

This was specifically relevant for the energy-procurement disruption for Europe. To the extent that Europe was able to buy energy from elsewhere, it was displacing barrels of oil and liquified natural gas (LNG) that other countries could buy, especially lower-middle-income countries. That was a tremendous impetus to inflation.

Having said that, if we take a step back and look at the federal funds rates from 2015 to 2019, pre-pandemic, we see that the neutral rate for the United States was between 3.5% and 4.5%. That equates to a 1% to 1.5% real rate plus 2% inflation.

The U.S. Federal Reserve (Fed) started 2022 with rates basically at zero, so it needed to move to a neutral position very quickly. Despite the significant tightening of its rhetoric since June, at the end of the year we’re at the upper end of this range. This means we’re basically in the band of neutral rates.

Now, do we stop at 5%? Do we stop at 4.75%? The basic point here is that despite all the rhetoric, the volatility, and the unpredictability of the geopolitical disruptions, we are essentially in line with where we think the neutral rate should be, even based on pre-COVID assumptions.

Hugo: How do you define the neutral rate?

Olga: It’s the nominal rate minus inflation. For the United States, as a developed economy, its real rate should be somewhere on the order of 1% to 1.5%. It’s not too restrictive and not too accommodative. If inflation is 2% to 3%, that puts the nominal rate between 3.5% and 4.5%.

Hugo: The strength of nominal GDP growth in the United States, you were clear in saying, could happen. You said interest rates have ended up at a neutral rate, but the speed of rate increases seems unusual. It’s not often that you see rates move so much in one year, at such a clip, with 75-basis-point increases.

Were you surprised, as you look back, at the pace of interest rate increases? For anyone who started their investing career in 2010 or even 2000, it’s not what they’re used to.

I think the idea right now that the Fed is going to overtighten and then have to start loosening right away is either a misinterpretation or wishful thinking.

Olga: I was surprised, in part, because I didn’t think about it very much. I knew where the rates were, and I knew where they needed to go. I underappreciated the speed with which the Fed was going to get us there.

Had inflation been lower, or had Russia-Ukraine not happened, perhaps the Fed would have had the opportunity to take 12 months to get to the neutral rate rather than six months. So, I definitely did not think about the 75-basis-point increases.

Having said that, front-loading like this makes a lot of sense. Monetary policy works with a lag of nine months to a year. You want to get to the neutral rate quickly and then hang out there for a long period of time. I think the idea right now that the Fed is going to overtighten and then have to start loosening right away is either a misinterpretation or wishful thinking.

I do expect the Fed may start decelerating the pace of tightening and then stop at whatever point it deems necessary, whether that’s in December, February, or March, and then just keep rates at that level for years.

Hugo: This equilibrium you’re describing is not inimical to investors such as ourselves, who are focused on quality growth, if we’ve got stable rates and a stable yield curve, and then enough growth in earnings to extract a decent total shareholder return. You might not get any help from multiples, but you’re not going to get any hindrance, either.

Olga: That’s exactly right. In fact, 2003 to 2007 was exactly that kind of expansion that you are highlighting. Rates had increased from something like 1% to over 5%. They were briefly higher than the 10-year rate. During that entire time, we saw very little derating, and the entirety of stock market returns was driven by earnings growth. That’s exactly what you would normally expect in an expansion. Where you get multiple reratings, where investors significantly increase their expectations for stock price multiples, is really only typically in recoveries—a very short but highly accretive period of time. An ordinary expansion is usually all about earnings growth, so this could be potentially very good for us.

Hugo: Has the complexion of earnings growth this year been different from what you expected? Have some sectors grown their revenues more than you would have thought while other sectors disappointed?

The energy sector has had positive revisions, and the technology sector has had negative revisions. The levels of growth at the start of the year may well have been different between those two, but the rate of change, where we’ve seen more or less growth than you expected, might be surprising.

Olga: Again, we did not forecast the Russia-Ukraine conflict, and, therefore, we did not expect the massive uptick in energy prices. As a result, we did not expect the significant earnings growth out of the energy sector.

I was much less surprised by the downward revisions for the technology sector. In the second half of last year, it was already apparent that both nominal and real growth had topped. You could see it at particular companies, but it also was becoming increasingly obvious at the industry level where cohorts of companies over-earned in the pandemic. Growth was going to decelerate sharply to, if not pre-pandemic rates of growth, something a lot closer to it. That’s effectively what we saw play out.

If you recall, when thinking about our multiples, we were benchmarking things to 2019 levels, exactly to take into account the pandemic overearnings. That story has mostly played out—maybe not for every company, but that has largely been the case.

Hugo: OK, we’ve talked about interest rates, nominal GDP, earnings growth, and energy prices.

What about the dollar? By the way, Olga, why is the dollar called the dollar?

Olga: I don’t know. Let’s Google it. “Origin and history of the word ‘dollar’ and dollar sign.” This is very cool. It’s actually from University of Exeter on the history of money.

The dollar is an Americanized or Anglicized form of “thaler,” the name of a coin minted in 1519 in Bohemia, what is now effectively the Czech Republic.

How did they get from thaler to dollar? I’m not sure.

It’s only after Europe had secured enough LNG supply and begun to address its need for LNG import terminals that we are starting to see cracks in that story of dollar appreciation.

Hugo: Anyway, another manifestation of the strength of nominal GDP in the United States is the strength of the dollar—or the wrecking ball dollar, as we call it. That has reverberated around the world. Are you surprised by how persistently strong the dollar has been?

Olga: Yes and no. I am becoming more of a typical economist by the day; it’s terrible.

Because we did not forecast the Russia-Ukraine conflict and we did not expect an upsurge in prices of fossil fuels, especially gas, given the massive supply disruptions, we did not expect a much stronger dollar.

Once the war broke out, and once we saw by April or May that the cost to Europe of procuring energy was going to be two to three times higher than it had been used to, that’s where you saw a continued rapid appreciation of the dollar. It’s only after Europe had secured enough LNG supply and begun to address its need for LNG import terminals that we are starting to see cracks in that story of dollar appreciation.

Hugo: Final question. Are you surprised there hasn’t been a major credit event, given the sharp rise in interest rates and the strength of dollar? Or is the recent crypto implosion the credit event?

Olga: Well, we really won’t know until it’s over. Earlier in the year, we saw balance-of-payment difficulties in some of the frontier and more emerging economies, such as Sri Lanka. The Philippines, Pakistan, and Egypt are also experiencing difficulties of their own. Some of them have asked the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for help. At the time, everybody says, “Is this the credit event?”

Now we have the crypto implosion, and this may prove to be the credit event. We saw a non-negligible selloff in the gilts market in the United Kingdom. You know this all too well, living in London. Was that the credit event? These are all relatively small and isolated. These are not systemic events.

Hopefully this will be it, or there will be a series of similarly small and contained events. But we really won’t know until the Fed is truly well and done tightening.

Olga Bitel, partner, is a global strategist on William Blair’s global equity team.

Hugo Scott‐Gall, partner, is a portfolio manager and co-director of research on William Blair’s global equity team.

Want more insights on the economy and investment landscape? Subscribe to our blog.

The post Lessons From a Chaotic Year appeared first on William Blair.

dollar

inflation

monetary

reserve

policy

interest rates

fed

monetary policy

inflationary

Argentina Is One of the Most Regulated Countries in the World

In the coming days and weeks, we can expect further, far‐reaching reform proposals that will go through the Argentine congress.

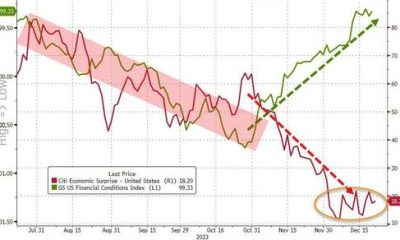

Crypto, Crude, & Crap Stocks Rally As Yield Curve Steepens, Rate-Cut Hopes Soar

Crypto, Crude, & Crap Stocks Rally As Yield Curve Steepens, Rate-Cut Hopes Soar

A weird week of macro data – strong jobless claims but…

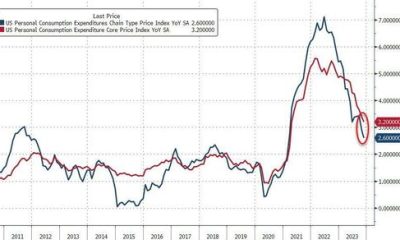

Fed Pivot: A Blend of Confidence and Folly

Fed Pivot: Charting a New Course in Economic Strategy Dec 22, 2023 Introduction In the dynamic world of economics, the Federal Reserve, the central bank…