Economics

Hoover Monetary Policy Conference

Friday May 12 we had the annual Hoover monetary policy conference. Hoover twitter stream here. Conference webpage and schedule here. As before, the talks,…

Friday May 12 we had the annual Hoover monetary policy conference. Hoover twitter stream here. Conference webpage and schedule here. As before, the talks, panels, and comments will eventually be written and published, and video should be available.

The Fed has experienced two dramatic institutional failures: Inflation peaking at 8%, and a rash of bank failures. There were panels focused on each, and much surrounding discussion.

We started with a little celebration of the 30th anniversary of Taylor (1993), which put the Taylor rule on the map. As Andy Levin pointed out in the discussion, academic immortality comes when they omit the number after your name. Rich Clarida, Volker Weiland and I quickly outlined some academic influence. John Lipsky added some very interesting commentary on how the Taylor rule was important on Wall Street, and specifically from his experience at Salomon Bros.

The second panel on financial regulation was a smash. Anat Admati chaired, with presentations by Darrell Duffie, Randy Quarles, and Amit Seru.

Duffie showed how online banking has taken over, and the combination of twitter and online banking makes runs happen much faster than before. You don’t have to stand in line, you can all push “withdraw” at once. He also showed a glaring hole in liquidity regulations: A bank cannot count as liquidity its ability to use the discount window at the Fed.

Seru covered some of his recent work, showing just how many banks have lost 10% or more of their asset value, and thus the value of their equity. (Nobody mentioned commercial real estate, the next shoe to drop.) They gently disagreed, Darrel viewing more liquidity and better liquidity rules as the main solution, and Amit more equity. All seemed to agree that the current regulatory mechanism is fundamentally broken.

Randy gave a thoughtful, eloquent, and impassioned talk laying to rest the common notion that “deregulation” caused SVB to fail. It would have passed all the stress tests. This will be important to read when the papers are all available. I take the implication that the regulatory structure is, again, fundamentally broken. No, more of the current regulations would not have helped. But Randy didn’t say that.

Peter Henry next presented “Disinflation and the Stock Market: Third World Lessons for First World Monetary Policy” (a paper with Anusha Chari), discussed by Josh Rauh and Chaired by Bill Nelson. A key innovation, they use stock market reactions to measure whether disinflations are a success on a cost/benefit basis. Large inflations seem to end with stock market expansions. Moderate disinflations don’t really do much for stock markets. Most disinflationary reforms fail.

Over lunch, Haruhiko Kuroda, Former Governor, Bank of Japan updated us on the Japanese situation. He is confident 2% inflation will return soon.

Niall Ferguson and Paul Schmelzing presented “The Safety Net: Central Bank Balance Sheets and Financial Crises 1587-2020,” (with Martin Kornejew and Moritz Schularick), with Barry Eichengreen discussing and Michael Bordo chair. A taste:

The title of the conference “How to Get Back on Track: A Policy Conference” is potent. Its intent and ambiguity are striking. First, the title presupposes that U.S. monetary policy is currently on the wrong track. Second, the webpage for this conference advances a puzzling definition of the phrase “on track.” How so? According to the Hoover webpage, “A key goal of the conference is to examine how to get back on track and, thereby, how to reduce the inflation rate without slowing down economic growth” (emphasis added).1 As this audience knows, there are macroeconomic models that permit disinflation with no slowdown in economic growth, but the assumptions underlying these models are very strong. It’s not clear, at least to me, why such a strict metric would be used to assess real-world monetary policymaking….

I loved this. It shows he took the time to read up on the conference, and I love seeing basic premises challenged. Later, this struck me as thoughtful:

I want to share with you a few strategic principles that are important to me. First, policymakers should be ready to react to a wide range of economic conditions with respect to inflation, unemployment, economic growth, and financial stability. The unprecedented pandemic shock is a good reminder that under extraordinary circumstances it will be difficult to formulate precise forecasts in real time. Our dual mandate from the Congress is especially helpful here. It provides the foundation for all our policy decisions. Second, policymakers should clearly communicate monetary policy decisions to the public. Our commitment to transparency should be evident to the public, and monetary policy should be conducted in a way that anchors longer-term inflation expectations. Third—and this is where I am revealing my passion for econometrics—policymakers should continuously update their priors about how the economy works as new data become available. In other words, it is appropriate to change one’s perspective as new facts emerge. In this sense, I am in favor of a Bayesian approach to information processing.

inflation

monetary

markets

policy

fed

central bank

monetary policy

Argentina Is One of the Most Regulated Countries in the World

In the coming days and weeks, we can expect further, far‐reaching reform proposals that will go through the Argentine congress.

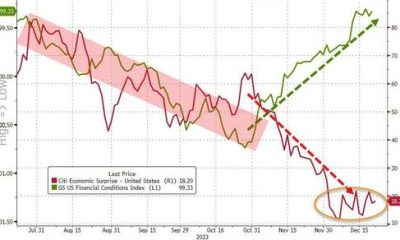

Crypto, Crude, & Crap Stocks Rally As Yield Curve Steepens, Rate-Cut Hopes Soar

Crypto, Crude, & Crap Stocks Rally As Yield Curve Steepens, Rate-Cut Hopes Soar

A weird week of macro data – strong jobless claims but…

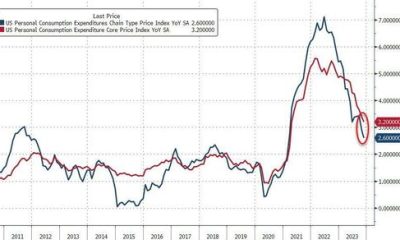

Fed Pivot: A Blend of Confidence and Folly

Fed Pivot: Charting a New Course in Economic Strategy Dec 22, 2023 Introduction In the dynamic world of economics, the Federal Reserve, the central bank…