Economics

Heterogeneous Agent Fiscal Theory

Today, I’ll add an entry to my occasional reviews of interesting academic papers. The paper: "Price Level and Inflation Dynamics in Heterogeneous Agent…

Today, I’ll add an entry to my occasional reviews of interesting academic papers. The paper: “Price Level and Inflation Dynamics in Heterogeneous Agent Economies,” by Greg Kaplan, Georgios Nikolakoudis and Gianluca Violante.

One of the many reasons I am excited about this paper is that it unites fiscal theory of the price level with heterogeneous agent economics. And it shows how heterogeneity matters. There has been a lot of work on “heterogeneous agent new-Keynesian” models (HANK). This paper inaugurates heterogeneous agent fiscal theory models. Let’s call them HAFT.

The paper has a beautifully stripped down model. Prices are flexible, and the price level is set by fiscal theory. People face uninsurable income shocks, however, and a borrowing limit. So they save an extra amount in order to self-insure against bad times. Government bonds are the only asset in the model, so this extra saving pushes down the interest rate, discount rate, and government service debt cost. The model has a time-zero shock and then no aggregate uncertainty.

This is exactly the right place to start. In the end, of course, we want fiscal theory, heterogeneous agents, and sticky prices to add inflation dynamics. And on top of that, whatever DSGE smorgasbord is important to the issues at hand; production side, international trade, multiple real assets, financial fractions, and more. But the genius of a great paper is to start with the minimal model.

Part II effects of fiscal shocks.

I am most excited by part II, the effects of fiscal shocks. This goes straight to important policy questions.

At time 0, the government drops $5 trillion of extra debt on people, with no plans to pay it back. The interest rate does not change. What happens? In the representative agent economy, the price level jumps, just enough to inflate away outstanding debt by $5 trillion.

(In this simulation, inflation subsequent to the price level jump is just set by the central bank, via an interest rate target. So the rising price level line of the representative agent (orange) benchmark is not that interesting. It’s not a conventional impulse response showing the change after the shock; it’s the actual path after the shock. The difference between colored heterogeneous agent lines and the orange representative agent line is the important part.)

Punchline: In the heterogeneous agent economies, the price level jumps a good deal more. And if transfers are targeted to the bottom of the wealth distribution, the price level jumps more still. It matters who gets the money.

This is the first step on an important policy question. Why was the 2020-2021 stimulus so much more inflationary than, say 2008? I have a lot of stories (“fiscal histories,” FTPL), one of which is a vague sense that printing money and sending people checks has more effect than borrowing in treasury markets and spending the results. This graph makes that sense precise. Sending people checks, especially people who are on the edge, does generate more inflation.

In the end, whether government debt is inflationary or not comes down to whether people treat the asset as a good savings vehicle, and hang on to it, or try to spend it, thereby driving up prices. Sending checks to people likely to spend it gives more inflation.

As you can see, the model also introduces some dynamics, where in this simple setup (flexible prices) the RA model just gives a price level jump. To understand those dynamics, and more intuition of the model, look at the response of real debt and the real interest rate

The greater inflation means that the same increase in nominal debt is a lesser increase in real debt. Now, the crucial feature of the model steps in: due to self-insurance, there is essentially a liquidity value of debt. If you have less debt, the marginal value of higher; people bid down the real interest rate in an attempt to get more debt. But the higher real rate means the real value of debt rises, and as the debt rises, the real interest rate falls.

To understand why this is the equilibrium, it’s worth looking at the debt accumulation equation, [ frac{db}{dt} = r_t (b_t; g_t) b_t – s_t. ](b_t) is the real value of nominal debt, (r_t=i_t-pi_t) is the real interest rate, and (s_t) is the real primary surplus. Higher real rates (debt service costs) raise debt. Higher primary surpluses pay down debt. Crucially — the whole point of the paper — the interest rate depends on how much debt is outstanding and on the distribution of wealth (g_t). ((g_t) is a whole distribution.) More debt means a higher interest rate. More debt does a better job of satisfying self-insurance motives. Then the marginal value of debt is lower, so people don’t try to save as much, and the interest rate rises. It works a lot like money demand,

Now, if the transfer were proportional to current wealth, nothing would change, the price level would jump just like the RA (orange) line. But it isn’t; in both cases more-constrained people get more money. The liquidity constraints are less binding, they’re willing to save more. For given aggregate debt the real interest rate will rise. So the orange line with no change in real debt is no longer a steady state. We must have, initially (db/dt>0.) Once debt rises and the distribution of wealth mixes, we go back to the old steady state, so real debt rises less initially, so it can continue to rise. And to do that, we need a larger price level jump. Whew. (I hope I got that right. Intuition is hard!)

In a previous post on heterogeneous agent models, I asked whether HA matters for aggregates, or whether it is just about distributional consequences of unchanged aggregate dynamics. Here is a great example in which HA matters for aggregates, both for the size and for the dynamics of the effects.

Here’s a second cool simulation. What if, rather than a lump-sum helicopter drop with no change in surpluses, the government just starts running permanent primary deficits?

In the RA model, a decline in surpluses is exactly the same thing as a rise in debt. You get the initial price jump, and then the same inflation following the interest rate target. Not so the HA models! Perpetual deficits are different from a jump in debt with no change in deficit.

Again, real debt and the real rate help to understand the intuition. The real amount of debt is permanently lower. That means people are more starved for buffer stock assets, and bid down the real interest rate. The nominal rate is fixed, by assumption in this simulation, so a lower real rate means more inflation.

For policy, this is an important result. With flexible prices, RA fiscal theory only gives a one-time price level jump in response to unexpected fiscal shocks. It does not give steady inflation in response to steady deficits. Here we do have steady inflation in response to steady deficits! It also shows an instance of the general “discount rates matter” theorem. Granted, here, the central bank could lower inflation by just lowering the nominal rate target but we know that’s not so easy when we add realisms to the model.

To see just why this is the equilibrium, and why surpluses are different than debt, again go back to the debt accumulation equation, [ frac{db}{dt} = r_t (b_t, g_t) b_t – s_t. ] In the RA model, the price level jumps so that (b_t) jumps down, and then with smaller (s_t), (r b_t – s_t) is unchanged with a constant (r). But in the HA model, the lower value of (b) means less liquidity value of debt, and people try to save, bidding down the interest rate. We need to work down the debt demand curve, driving down the real interest costs (r) until they partially pay for some of the deficits. There is a sense in which “financial repression” (artificially low interest rates) via perpetual inflation help to pay for perpetual deficits. Wow!

Part I r<g

The first theory part of the paper is also interesting. (Though these are really two papers stapled together, since as I see it the theory in the first part is not at all necessary for the simulations.) Here, Kaplan, Nikolakoudis and Violante take on the r<g question clearly. No, r<g does not doom fiscal theory! I was so enthused by this that I wrote up a little note “fiscal theory with negative interest rates” here. Detailed algebra of my points below are in that note, (An essay r<g and also a r<g chapter in FTPL explains the related issue, why it’s a mistake to use averages from our real economy to calibrate perfect foresight models. Yes, we can observe (E(r)<E(g)) yet present values converge.)

I’ll give the basic idea here. To keep it simple, think about the question what happens with a negative real interest rate (r<0), a constant surplus (s) in an economy with no growth, and perfect foresight. You might think we’re in trouble: [b_t = frac{B_t}{P_t} = int e^{-rtau} s dtau = frac{s}{r}.]A negative interest rate makes present values blow up, no? Well, what about a permanently negative surplus (s<0) financed by a permanently negative interest cost (r<0)? That sounds fine in flow terms, but it’s really weird as a present value, no?

Yes, it is weird. Debt accumulates at [frac{db_t}{dt} = r_t b_t – s_t.] If (r>0), (s>0), then the real value of debt is generically explosive for any initial debt but (b_0=s/r). Because of the transversality condition ruling out real explosions, the initial price level jumps so (b_0=B_0/P_0=s/r). But if (r<0), (s<0), then debt is stable. For any (b_0), debt converges, the transversality condition is satisfied. We lose fiscal price level determination. No, you can’t take a present value of a negative cashflow stream with a negative discount rate and get a sensible present value.

But (r) is not constant. The more debt, the higher the interest rate. So [frac{db_t}{dt} = r(b_t) b_t – s_t.] Linearizing around the steady state (b=s/r), [frac{db_t}{dt} = left[r_t + frac{dr(b_t)}{db}right]b_t – s.] So even if (r<0), if more debt raises the interest rate enough, if (dr(b)/db) is large enough, dynamics are locally and it turns out globally unstable even with (r<0). Fiscal theory still works!

You can work out an easy example with bonds in utility, (int e^{-rho t}[u(c_t) + theta v(b_t)]dt), and simplifying further log utility (u(c) + theta log(b)). In this case (r = rho – theta v'(b) = rho – theta/b) (see the note for derivation), so debt evolves as [frac{db}{dt} = left[rho – frac{theta}{b_t}right]b_t – s = rho b_t – theta – s.]Now the (r<0) part still gives stable dynamics and multiple equilibria. But if (theta>-s), then dynamics are again explosive for all but (b=s/r) and fiscal theory works anyway.

This is a powerful result. We usually think that in perfect foresight models, (r>g), (r>0) here, and consequently positive vs negative primary surpluses (s>0) vs. (s<0) is an important dividing line. I don’t know how many fiscal theory critiques I have heard that say a) it doesn’t work because r<g so present values explode b) it doesn’t work because primary surpluses are always slightly negative.

This is all wrong. The analysis, as in this example, shows is that fiscal theory can work fine, and doesn’t even notice, a transition from (r>0) to (r<0), from (s>0) to (s<0). Financing a steady small negative primary surplus with a steady small negative interest rate, or (r<g) is seamless.

The crucial question in this example is (s<-theta). At this boundary, there is no equilibrium any more. You can finance only so much primary deficit by financial repression, i.e. squeezing down the amount of debt so its liquidity value is high, pushing down the interest costs of debt.

The paper staples these two exercises together, and calibrates the above simulations to (s<0) and (r<g). But I bet they would look almost exactly the same with (s>0) and (r>g). (r<g) is not essential to the fiscal simulations.

The paper analyzes self-insurance against idiosyncratic shocks as the cause of a liquidity value of debt. That’s interesting, and allows the authors to calibrate the liquidity value against microeconomic observations on just how much people suffer such shocks and want to insure against them. The Part I simulations are just that, heterogeneous agents in action. But this theoretical point is much broader, and applies to any economic force that pushes up the real interest rate as the volume of debt rises. Bonds in utility, here and in the paper’s appendix, work. They are a common stand in for the usefulness of government bonds in financial transactions. And in that case, it’s easier to extend the analysis to a capital stock, real estate, foreign borrowing and lending, gold bars, crypto, and other means of self-insuring against shocks. Standard “crowding out” stories by which higher debt raises interest rates work. (Blachard’s r<g work has a lot of such stories.) The “segmented markets” stories underlying faith in QE give a rising b(r). So the general principle is robust to many different kinds of models.

My note explores one issue the paper does not, and it’s an important one in asset pricing. OK, I see how dynamics are locally unstable, but how do you take a present value when r<0? If we write the steady state [b_t = int_{tau=0}^infty e^{-r tau}s dtau = int_{tau=0}^T e^{-r tau}s dtau + e^{-rT}b_{t+T}= (1-e^{-rT})frac{s}{r} + e^{-rT}b,]and with (r<0) and (s<0), the integral and final term of the present value formula each explode to infinity. It seems you really can’t discount with a negative rate.

The answer is: don’t integrate forward [frac{db_t}{dt}=r b_t – s ]to the nonsense [ b_t = int e^{-r tau} s dtau.]Instead, integrate forward [frac{db_t}{dt} = rho b_t – theta – s]to [b_t = int e^{-rho tau} (s + theta)dt = int e^{-rho tau} frac{u'(c_t+tau)}{u'(c_t)}(s + theta)dt.]In the last equation I put consumption ((c_t=1) in the model) for clarity.

- Discount the flow value of liquidity benefits at the consumer’s intertemporal marginal rate of substitution. Do not use liquidity to produce an altered discount rate.

This is another deep, and frequently violated point. Our discount factor tricks do not work in infinite-horizon models. (1=E(R_{t+1}^{-1}R_{t+1})) works just as well as (1 = Eleft[beta u'(c_{t+1})/u'(c_t)right] r_{t+1}) in a finite horizon model, but you can’t always use (m_{t+1}=R_{t+1}^{-1}) in infinite period models. The integrals blow up, as in the example.

This is a good thesis topic for a theoretically minded researcher. It’s something about Hilbert spaces. Though I wrote the discount factor book, I don’t know how to extend discount factor tricks to infinite periods. As far as I can tell, nobody else does either. It’s not in Duffie’s book.

In the meantime, if you use discount factor tricks like affine models — anything but the proper SDF — to discount an infinite cashflow, and you find “puzzles,” and “bubbles,” you’re on thin ice. There are lots of papers making this mistake.

A minor criticism: The paper doesn’t show nuts and bolts of how to calculate a HAFT model, even in the simplest example. Note by contrast how trivial it is to calculate a bonds in utility model that gets most of the same results. Give us a recipe book for calculating textbook examples, please!

Obviously this is a first step. As FTPL quickly adds sticky prices to get reasonable inflation dynamics, so should HAFT. For FTPL (or FTMP, fiscal theory of monetary policy; i.e. adding interest rate targets), adding sticky prices made the story much more realistic: We get a year or two of steady inflation eating away at bond values, rather than a price level jump. I can’t wait to see HAFT with sticky prices. For all the other requests for generalization: you just found your thesis topic.

Send typos, especially in equations.

gold

inflation

monetary

markets

policy

interest rates

central bank

negative interest rates

monetary policy

inflationary

Argentina Is One of the Most Regulated Countries in the World

In the coming days and weeks, we can expect further, far‐reaching reform proposals that will go through the Argentine congress.

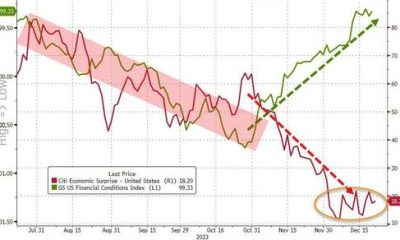

Crypto, Crude, & Crap Stocks Rally As Yield Curve Steepens, Rate-Cut Hopes Soar

Crypto, Crude, & Crap Stocks Rally As Yield Curve Steepens, Rate-Cut Hopes Soar

A weird week of macro data – strong jobless claims but…

Fed Pivot: A Blend of Confidence and Folly

Fed Pivot: Charting a New Course in Economic Strategy Dec 22, 2023 Introduction In the dynamic world of economics, the Federal Reserve, the central bank…