Economics

Guest Contribution: “The Strong Dollar, Global Inflation, and Global Recession”

Today, we are pleased to present a guest contribution by Steven Kamin (AEI), formerly Director of the Division of International Finance at the Federal…

Today, we are pleased to present a guest contribution by Steven Kamin (AEI), formerly Director of the Division of International Finance at the Federal Reserve Board. The views presented represent those of the authors, and not necessarily those of the institutions the authors are affiliated with.

In recent months, there has been a great deal of discussion in the financial media about how aggressive Fed tightening has pushed up the dollar and poses (at least) two dangerous consequence for the global economy. First, higher U.S. interest rates and a stronger dollar are creating difficulties for emerging market economies (EMEs), which must buy dollars to repay their dollar debts with cheaper local currencies. And, second, those cheaper currencies, in advanced as well as emerging market economies, are boosting import costs, adding to already-strong inflationary pressures, and forcing foreign central banks to tighten their own monetary policies. Both these developments purportedly are pushing the world into global recession.

There is some truth to these concerns. A rising dollar is one of the channels through which U.S. monetary policy tightening helps cool the economy, and this inevitably involves exporting a certain amount of our inflation to other economies. It is also true that, historically, tighter Fed policies have meant bad news for EMEs: plunging currencies, rising credit spreads, and disruptive capital outflows.

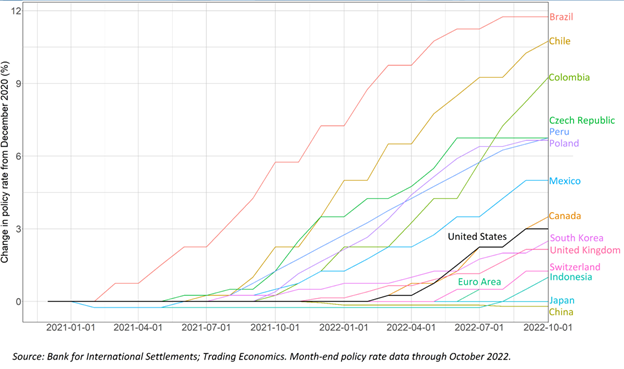

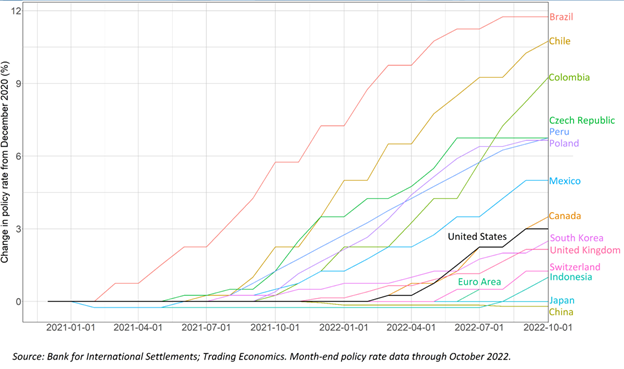

However, as I explore in my recent note, Will the Strong Dollar Trigger a Global Recession, much of the current discussion exaggerates the role of Fed tightening and dollar appreciation in darkening prospects for the world economy. First, contrary to the impression conveyed by many commentators that the Fed has been exceptionally aggressive, central banks in many countries started tightening monetary policy before the Fed and most of them raised rates by a great deal more.

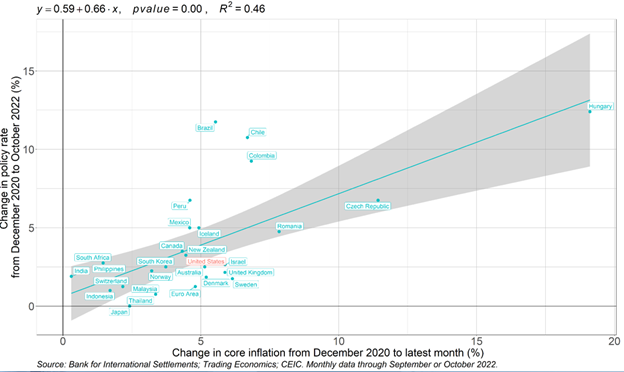

Countries with larger increases in core inflation (excluding food and energy) generally implemented larger increases in interest rates—the Fed’s response to inflation has been very much in line with that relationship.

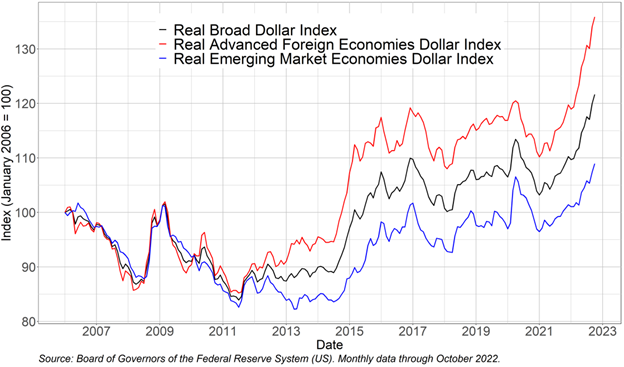

Second, the strong dollar is putting less pressure on EMEs than is generally believed. Most discussions of this issue focus on the dollar’s value against the currencies of the advanced economies. Even after giving up some of its gains in the past week, this is up about 15 percent since the beginning of 2021, based on Federal Reserve data. By contrast, the value of the dollar against the currencies of our EME trading partners is up only about 8 percent over the same period.

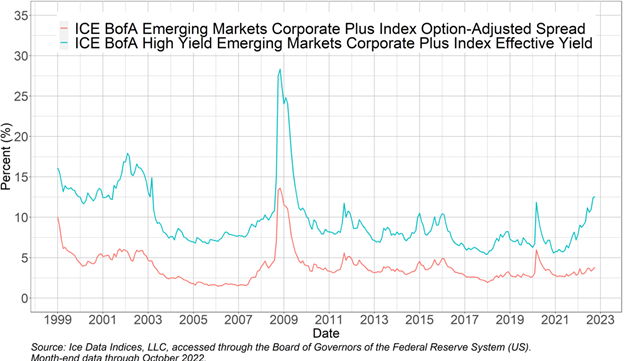

This smaller rise in the dollar against the EMEs translates into a smaller rise in their debt burden. Indeed, so far this year, most of the major EMEs have held up reasonably well. As shown below, credit spreads over U.S. Treasuries on dollar debt owed by EMEs, a good measure of the market’s assessment of their creditworthiness, have widened on average but generally remain with historical ranges. To be sure, high-yield spreads for especially fragile economies, such as Sri Lanka, Pakistan, and Argentina, are rising more, but these largely reflect their own fundamental imbalances and, in any event, are unlikely to drag the global economy into recession.

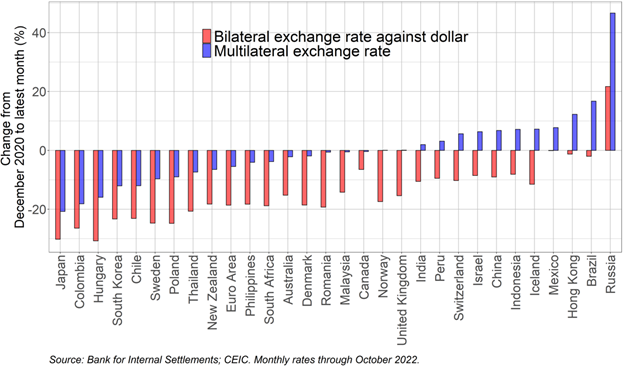

Finally, the role of the strong dollar in boosting inflation abroad has been exaggerated. Because nearly all currencies have fallen against the dollar, each foreign economy’s “multilateral exchange rate”—that is, its average exchange rate against all of its trading partners—has fallen by much less (or even risen) than its “bilateral” rate against the dollar. In consequence, the foreign economies experienced smaller increases in import costs and thus consumer prices than would be implied by the depreciations of their currencies against the dollar alone. (In addition to imports from the United States, commodity prices such as oil are also invoiced in dollars, but their prices generally fall when the dollar rises.) And this means that foreign central banks have had to tighten monetary policy by less.

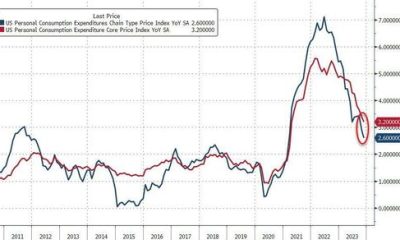

Summing up, the rise in the dollar poses challenges for the global economy, but those challenges should not be overstated. A narrow focus on the strong dollar underplays what are undoubtedly the more salient forces pushing the world economy toward recession: elevated energy and food costs; energy shortages, especially in Europe, resulting from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine; soaring inflation rates prompting central banks around the world to tighten monetary policy; China’s growth-strangling zero-COVID policy; and economic scarring and debt buildups left as the legacy of the COVID-19 pandemic.

This post written by Steven Kamin.

dollar

inflation

commodity

monetary

reserve

policy

interest rates

fed

monetary policy

inflationary

Argentina Is One of the Most Regulated Countries in the World

In the coming days and weeks, we can expect further, far‐reaching reform proposals that will go through the Argentine congress.

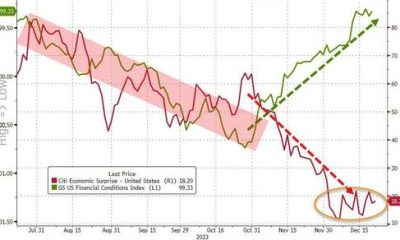

Crypto, Crude, & Crap Stocks Rally As Yield Curve Steepens, Rate-Cut Hopes Soar

Crypto, Crude, & Crap Stocks Rally As Yield Curve Steepens, Rate-Cut Hopes Soar

A weird week of macro data – strong jobless claims but…

Fed Pivot: A Blend of Confidence and Folly

Fed Pivot: Charting a New Course in Economic Strategy Dec 22, 2023 Introduction In the dynamic world of economics, the Federal Reserve, the central bank…