Economics

Guest Contribution: “The Fed Is Following the Taylor Rule”

Today, we present a guest post written by David Papell and Ruxandra Prodan, Professor and Instructional Associate Professor of Economics at the University…

Today, we present a guest post written by David Papell and Ruxandra Prodan, Professor and Instructional Associate Professor of Economics at the University of Houston.

The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) raised the target range for the federal funds rate (FFR) by 25 basis points to between 4.5 and 4.75 percent in its January/February 2023 meeting and anticipated that ongoing increases would be appropriate. This followed rate increases totaling 4.25 percentage points between March and December 2022 preceded by two years at the Effective Lower Bound (ELB).

There is widespread agreement that the Fed fell “behind the curve” by not raising rates when inflation rose in 2021, forcing it to play “catch-up” in 2022. “Behind the curve,” however, is meaningless without a measure of “on the curve.” In the latest version of our paper, “Policy Rules and Forward Guidance Following the Covid-19 Recession,” we use data from the Summary of Economic Projections (SEP) from September 2020 to December 2022 to compare policy rule prescriptions with actual and FOMC projections of the FFR. This provides a precise definition of “behind the curve” as the difference between the FFR prescribed by the policy rule and the actual or projected FFR. We analyze four policy rules:

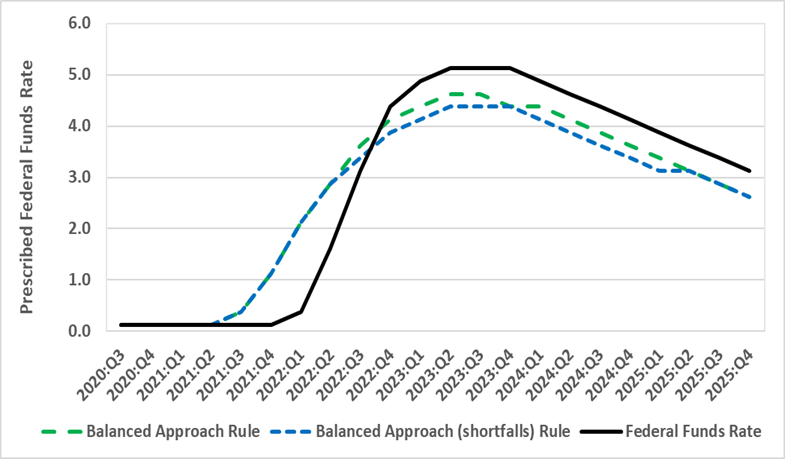

The Taylor (1993) rule with an unemployment gap is as follows,

where is the level of the short-term federal funds interest rate prescribed by the rule, is the inflation rate, is the 2 percent target level of inflation, is the 4 percent rate of unemployment in the longer run, is the current unemployment rate, and is the ½ percent neutral real interest rate from the current SEP.

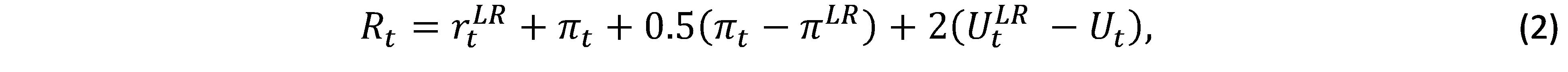

Yellen (2012) analyzed the balanced approach rule where the coefficient on the inflation gap is 0.5 but the coefficient on the unemployment gap is raised to 2.0.

The balanced approach rule received considerable attention following the Great Recession and became the standard policy rule used by the Fed.

The FOMC adopted a far-reaching Revised Statement on Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy in August 2020. The framework contains two major changes from the original 2012 statement. First, policy decisions will attempt to mitigate shortfalls, rather than deviations, of employment from its maximum level. Second, the FOMC will implement Flexible Average Inflation Targeting (FAIT) where, “following periods when inflation has been running persistently below 2 percent, appropriate monetary policy will likely aim to achieve inflation moderately above 2 percent for some time.”

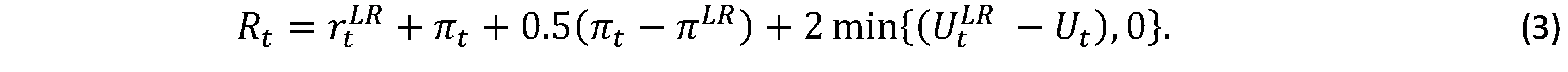

While most of the attention following the Revised Statement focused on FAIT, the large rise in inflation in 2021 and 2022 has made that part irrelevant. The balanced approach (shortfalls) rule was introduced in the February 2021 Monetary Policy Report (MPR). The rule mitigates employment shortfalls instead of deviations by having the FFR only respond to unemployment if it exceeds longer-run unemployment,

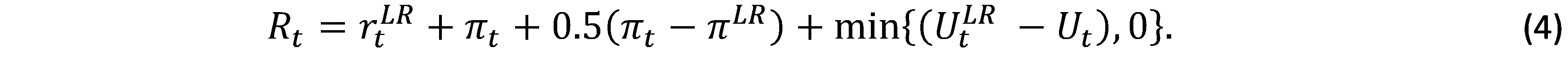

If unemployment exceeds longer-run unemployment, the FFR prescriptions are the same as with the balanced approach rule. If unemployment is below longer-run unemployment, the FOMC will not raise the FFR solely because of low unemployment. We also analyze a Taylor (shortfalls) rule,

These rules are non-inertial because the FFR fully adjusts whenever the target FFR changes. This is not in accord with FOMC practice to smooth rate increases when inflation rises. During 2021 and 2022, the non-inertial rules prescribe unrealistically large increases of the FFR.

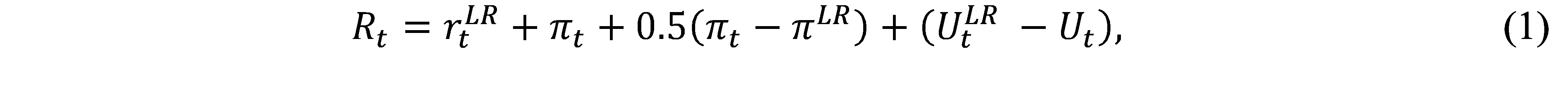

We specify inertial versions of the rules based on Clarida, Gali, and Gertler (1999),

where is the degree of inertia and is the target level of the federal funds rate prescribed by Equation (3). We set as in Bernanke, Kiley, and Roberts (2019). equals the rate prescribed by the rule if it is positive and zero if the prescribed rate is negative.

The figure depicts the midpoint for the target range of the FFR for September 2020 to December 2022 and the projected FFR for March 2023 to December 2025 from the December 2022 SEP. Following the exit from the ELB to 0.375 in March 2022, the FFR rose to 4.625 in February 2023 and is projected to rise to 5.125 in June 2023 before falling in 2024 and 2025.

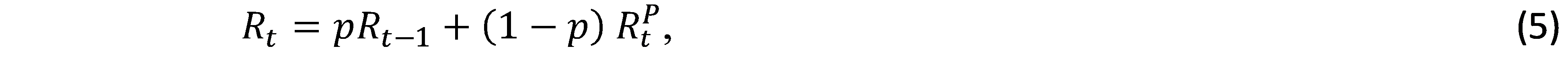

Figure 1, Panel A: Inertial Policy Rules and the Federal Funds Rate – Taylor Rule

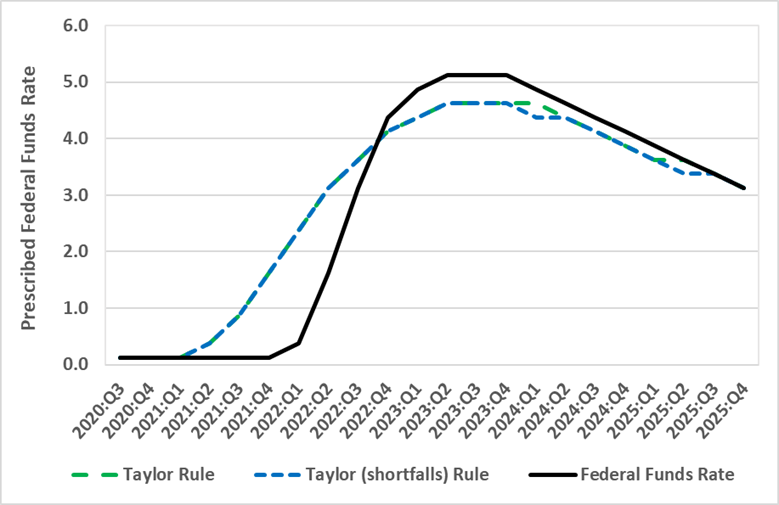

Policy rule prescriptions are reported in Panel A for the Taylor rules and Panel B for the balanced approach rules. Between September 2020 and December 2022, we use real-time inflation and unemployment data that was available at the time of the FOMC meetings. Between March 2023 and December 2025, we use inflation, unemployment, and real FFR in the longer-run projections from the December 2022 SEP.

Figure 1, Panel B: Inertial Policy Rules and the Federal Funds Rate – Balanced Approach Rules.

The FFR fell “behind the curve” when the prescribed FFR increased above the ELB in June 2021 for the Taylor rules and September 2021 for the balanced approach rules. The gap peaked at 200 basis points for the Taylor rules and 175 basis points for the balanced approach rules at the liftoff from the ELB in March 2022. As the FOMC aggressively raised the FFR, the gap narrowed to 25 basis points above the FFR in September 2022 for the balanced approach (shortfalls) rule and 50 basis points above the FFR for the other three rules.

We highlight two points illustrated in Figure 1. First, as described in more detail in the paper, the FOMC could have achieved the same increase in the FFR by September 2022 without resorting to 75 basis point rate increases by following any of the policy rules. Second, the balanced approach rules prescriptions are closer to the path of the FFR than the Taylor rules prescriptions.

The relation between the actual and prescribed FFR’s reversed in December 2022, as the FFR is 50 basis points above the prescribed FFR for the balanced approach (shortfalls) rule and 25 basis points above the FFR for the other three rules. For 2023 – 2025, the figure shows the FFR projected by the December 2022 SEP and the FFR prescribed by the policy rules using data projected from the December 2022 SEP. The gaps widen through December 2023 and then narrow as the FFR projections decrease.

The relation between the Taylor rule and balanced approach rule prescriptions also reverses with the December 2025 SEP, as the gaps between the FFR projections and the policy rule prescriptions are smaller for the Taylor rules than for the balanced approach rules. Starting in March 2024, the gaps for the Taylor rule narrow to 25 basis points and, between June and December of 2025, the Taylor rule prescriptions are equal to the FFR projections.

This post written by David Papell and Ruxandra Prodan.

Argentina Is One of the Most Regulated Countries in the World

In the coming days and weeks, we can expect further, far‐reaching reform proposals that will go through the Argentine congress.

Crypto, Crude, & Crap Stocks Rally As Yield Curve Steepens, Rate-Cut Hopes Soar

Crypto, Crude, & Crap Stocks Rally As Yield Curve Steepens, Rate-Cut Hopes Soar

A weird week of macro data – strong jobless claims but…

Fed Pivot: A Blend of Confidence and Folly

Fed Pivot: Charting a New Course in Economic Strategy Dec 22, 2023 Introduction In the dynamic world of economics, the Federal Reserve, the central bank…