Economics

Guest Contribution: “In god we trust, all the others must bring (good) collateral”

Today, we are pleased to present a guest contribution by Miklos Vari (Banque de France). The views expressed herein are those of the author and should…

Today, we are pleased to present a guest contribution by Miklos Vari (Banque de France). The views expressed herein are those of the author and should not be attributed to the Banque de France or the Eurosystem.

In the middle of SVB’s demise, some details got lost, and with them, potentially a lot of taxpayers’ money. The seemingly innocuous detail was announced by the Fed when it introduced its latest program, Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP) which intended to stem the panic:

“The additional funding will be made available through the creation of a new Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP), offering loans of up to one year in length to banks, savings associations, credit unions, and other eligible depository institutions pledging U.S. Treasuries, agency debt and mortgage-backed securities, and other qualifying assets as collateral. These assets will be valued at par.” (emphasis added).

What may seem like a small accounting convention that most people would not notice, could be a turning point for the Fed, and central banking in general. Indeed, the usual practice in central banks is to value bonds brought as collateral not at par, but using their market value, or the best estimate about their market value when they are not traded on liquid markets. This is because when central banks lend to banks, they ask for protections in case banks default. In case a bank fails, the central bank becomes the owner of the pledged collateral. Central banks recover the value of the asset by selling it on the market, or keeping it until maturity. Because currently the market value of bonds is generally strictly lower than their par value (also called face value), if a bank defaults, the central bank would make losses equal to the difference between par and market value. This difference can be attributed to unexpectedly fast increase of Fed interest rates since 2022, which mechanically depresses the market value of all bonds. To use the world of US authorities themselves:

“ As a result of the higher interest rates, longer term maturity assets acquired by banks when interest rates were lower are now worth less than their face values. “ (FDIC, 6 March 2023)

Some estimates allow us to get a sense of the magnitude of the gap. For instance data form the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas show that the market value of the stock of privately held gross federal debt stood $1.5 trillion below its par value, as of February 2023. The FDIC stated that US banks unrealized losses on securities stood at $620 billion as of end 2022.

When BTFP was introduced who could predict how many banks would borrow from it, fail to repay and leave collateral with market value strictly lower than the loans they contracted from the US central bank? Since its introduction, take-up at the facility has increased steadily, and stands above $68bn as of April 6th. So while it is impossible to know if the Fed will eventually make any loss, it is certain that it explicitly takes the risk of doing so by valuing collateral at par, and that this loss may reach around 8 cents (the difference between market and par value as of February 2023) on each dollar lent.

To be sure, these are no potential “paper losses”, “accounting losses” or “subjective losses” the Fed is exposing itself to. If failing banks leave only par-valued collateral in exchange for their defaulted loans, this would correspond to a loss of real economic resources for the US central bank.

The Fed would obviously make losses if it sells the acquired collateral on the market, but this would also be the case if it holds the debt until maturity. Stating that the market value of debt is below its par value, is equivalent to say that US debt is paying interest coupons that are below market rates (coupon/par value < market interest rates).

For example, in the events of a default, the Fed could own debt that yields 1% of the par value per year, while the Fed pays interests on its newly created liabilities (created to “fund” the loans to banks), currently between 4.8% and 4.9%. This negative interest rate carry over the life of the bond is equivalent to the difference between par value and market value.

This difference would cost the Fed, a public institution dearly. But does it matter that the Fed makes losses? I argue it does. The Fed enjoys a backing of $25 bn from a Treasury fund, also a taxpayer’s property.[1] Beyond these $25 bn, things get slightly more complicated, but not any better.

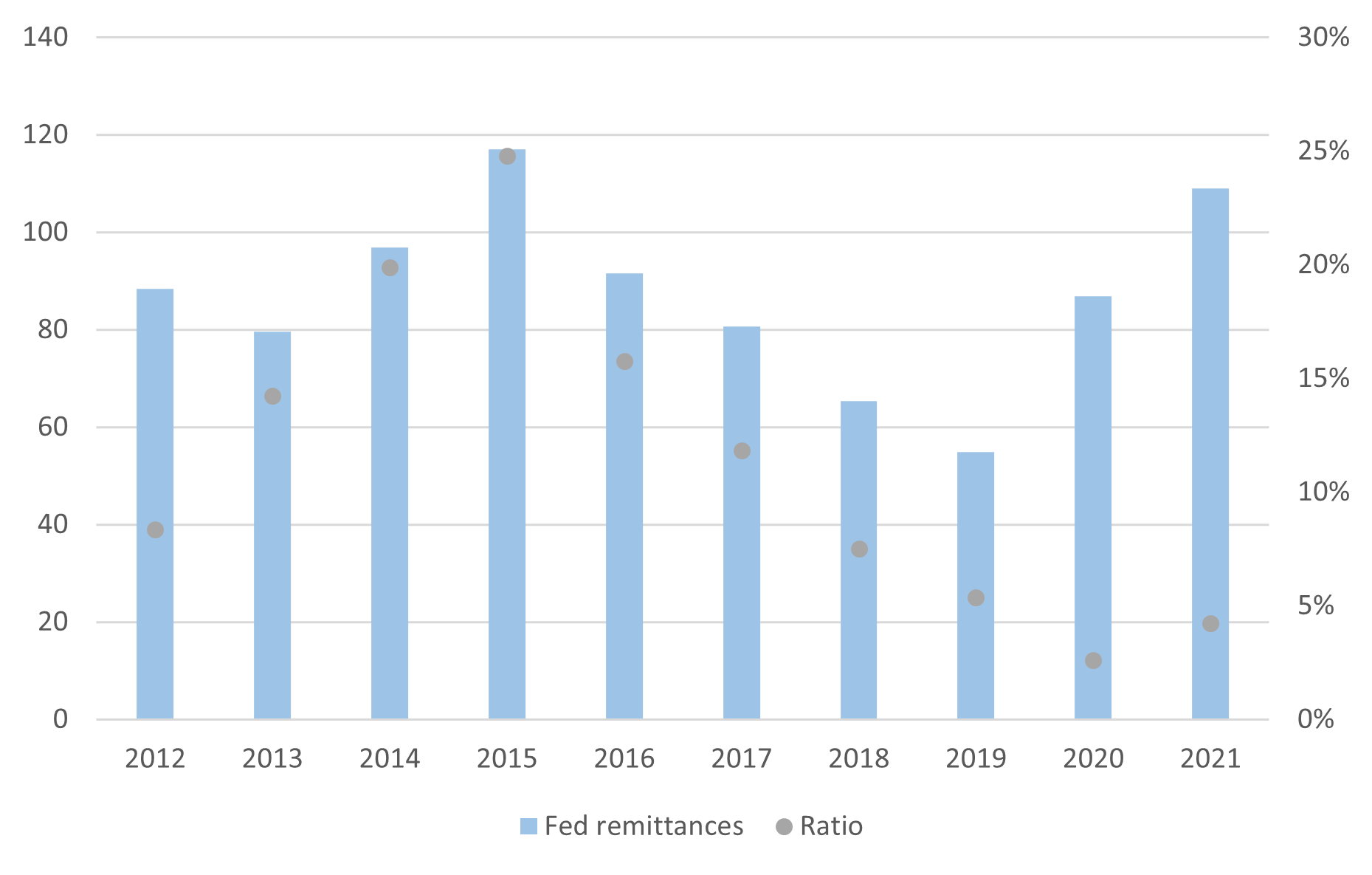

Over 2012-2021, the Fed remitted on average $87 bn per year (figure 1), or 11% of the total annual deficit, and up to 25% of the deficit in 2015. In other words, in 2015, absent any income from the Fed, the Federal deficit of the United-States would have been 25% higher. Higher deficit implies higher borrowings on the market, and more interest payments being made by the taxpayer to bondholders. In simple words: any Fed loss reduces payments to the Treasury by the same amount, increases the Federal deficit, forcing the Treasury to borrow more and pay more interests to creditors. The Federal Reserve System has already suspended payments to the Treasury after making losses on its bond portfolio in 2022. Any additional loss will push back the date at which it will resume the practice.

Valuing collateral at par is not potentially harmful only to the US taxpayer. It also sets a precedent for central banks in the rest of the world. The IMF promotes for all countries “Adequate valuation and risk control measures” when dealing with monetary policy collateral.[2] The Fed example might be replicated abroad. Beyond central banking, the Fed, an independent agency of the executive branch has taken a decision that may have important fiscal ramifications, and by this may be interfering with Congress’ “power of the purse”, a cause of concern for central banks independence and the division of power. I would conclude by invoking a moto I heard during my career in central banks : “In god we trust, all the others must bring (good) collateral”

Figure 1: Fed remittances to the Treasury (left-axis, in billion) and how it compared to the US Federal deficit over the same period (right-axis, percentage points)

Source: Fed annual reports for remittances, assuming that reported figures are for the calendar year (i.e. not the US fiscal year) and FRED monthly series for the deficit over the calendar year.

Notes

[1] The Congressional Research Services stated that “This could be controversial given that it is not the originally intended use of the fund and similar actions were prohibited in the past”.

[2]IM Staff Chailloux et al. (2008), also states that “valuation at face value is a simplified approach which is likely to significantly overvalue bank loans’ net present value”, which is basically true of any asset.

This post written by Miklos Vari.

dollar

monetary

markets

reserve

policy

interest rates

fed

central bank

monetary policy

Argentina Is One of the Most Regulated Countries in the World

In the coming days and weeks, we can expect further, far‐reaching reform proposals that will go through the Argentine congress.

Crypto, Crude, & Crap Stocks Rally As Yield Curve Steepens, Rate-Cut Hopes Soar

Crypto, Crude, & Crap Stocks Rally As Yield Curve Steepens, Rate-Cut Hopes Soar

A weird week of macro data – strong jobless claims but…

Fed Pivot: A Blend of Confidence and Folly

Fed Pivot: Charting a New Course in Economic Strategy Dec 22, 2023 Introduction In the dynamic world of economics, the Federal Reserve, the central bank…